by Western University's MA Public History Program Students

"The crowd of crazy fools"[1]

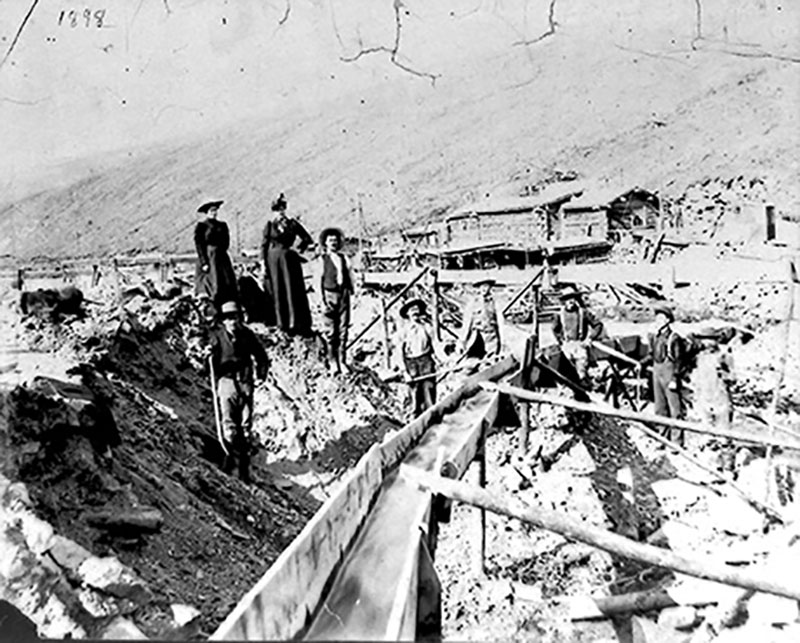

It was a strange scene in Dawson City in the summer of 1897. Amidst the ramshackle wooden buildings, the muddy streets, and the grime covered prospectors, a large white circus tent covered the space of a city block. Inside were such luxuries as a portable bowling alley, a soda machine, two dozen pigeons, and fine silver and china. The owners of the tent were two wealthy American ladies, Mary Hitchcock and Edith Van Buren, who had come to Dawson City not to make their fortune, but to experience first-hand the excitement of the Klondike Gold Rush.

The experiences of Hitchcock and Van Buren were far from common, however they illustrate the fervor of excitement that came with the discovery of gold in the Canadian West. When news broke of gold in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia in 1858, and again in the Klondike region of the Yukon in 1897, thousands of hopeful adventurers rushed to these remote corners of the Empire. Due to the close proximity of the United States, many of these people were Americans, representing such diverse backgrounds as farmers, merchants, and even some experienced miners from the California Gold Rush of 1849. The people who came, the life they made in the gold fields, and their impact on Aboriginal peoples all shaped the region for years to come.

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1965.2.7

“I wanted the gold, and I sought it”: The Inspiration to Leave[2]

The attraction of gold was a powerful one. The United States was in the midst of an economic recession, and Americans were reading newspaper stories about bankruptcy, unemployment, and poverty. When gold was discovered in British Columbia and the Yukon, readers were instead entranced by accounts of ordinary people striking it rich in the north.[3] Many travellers published personal accounts of their treks to the north, and these documents became widely available. Sharing in these adventures, and setting out on escapades of their own, was an opportunity that many found impossible to turn down.

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1984.216.56

Did You Know?

One couple made $30,000 (the equivalent of $500,000 in 2015) in one winter in the Yukon by selling coffee and pies.[4]

One of these men was John McIymont Whyte of Seattle, who had lost his business and home in the financial crash of the 1890s. By 1897 he was unemployed and although he obtained a degree from the University of Edinburgh, his family was living off the money earned by his twelve year-old son selling newspapers. Whyte left for the Klondike, and although he never made a fortune, he was able to find a steady job and eventually sent for his family to join him.[5] Whyte’s story is in many ways a typical one during the Klondike; an average person who never made a fortune, but succeeded in making a living.

"Dreamers From the Seven Seas": Who Took Part?[6]

The discovery of gold provided exciting opportunities for those who came seeking it, but for the authorities in charge of these regions the sudden influx of American stampeders was cause for concern. Before the gold rush in the Fraser Canyon, the region was dominated by the fur trade and had very little non-indigenous settlement. There were worries in the Hudson’s Bay Company that large numbers of primarily white American gold miners would undermine their control of the area, and maintaining British sovereignty was a central concern.

Would be gold miners to the Klondike were “dressed in the clothes of the trail - hideous red-and-yellow plaid mackinaws, overalls tucked into high boots, and caps of all descriptions."[7]

In an effort to diminish the effects of this influx of Americans, Governor James Douglas felt it necessary to increase the number of people in the colony who could be counted on to oppose threats of American expansion. In that vein, Governor Douglas sent Jeremiah Nagle, the captain of the steamship Commodore, to speak to a group of black Americans at a church in San Francisco. Nagle encouraged black persons to immigrate to British territory, and promised that those who did would be afforded British protection. Between these assurances and the promise of gold, thirty-five black men opted to take the next boat to Victoria.[8] In total, an estimated five hundred black individuals came to Victoria and the mainland, a number of whom made up Victoria’s first police force. The first large merchant house in Victoria to compete with the Hudson’s Bay Company was founded by two American blacks: Peter Lester and Mifflin Gibbs.[9]

Compared to an estimated 25,000 white men, there was also a lack of white women on the mainland of British Columbia in the early years of the gold rush. This presented a social risk, as white women were seen in British colonial society as a civilizing force. The British government was so invested in encouraging young women to immigrate to British Columbia that they chartered a ship from Britain to Vancouver Island in the hopes that they would marry men who were going to the gold mines.[10] The “bride-ship” Tynemouth did not have a lasting effect on the demography of British Columbia, if for no other reason than several of the sixty girls on board were too young to marry under colonial law.[11] Instead, some of the men in British Columbia married Aboriginal women, while others went to California looking for a spouse.[12]

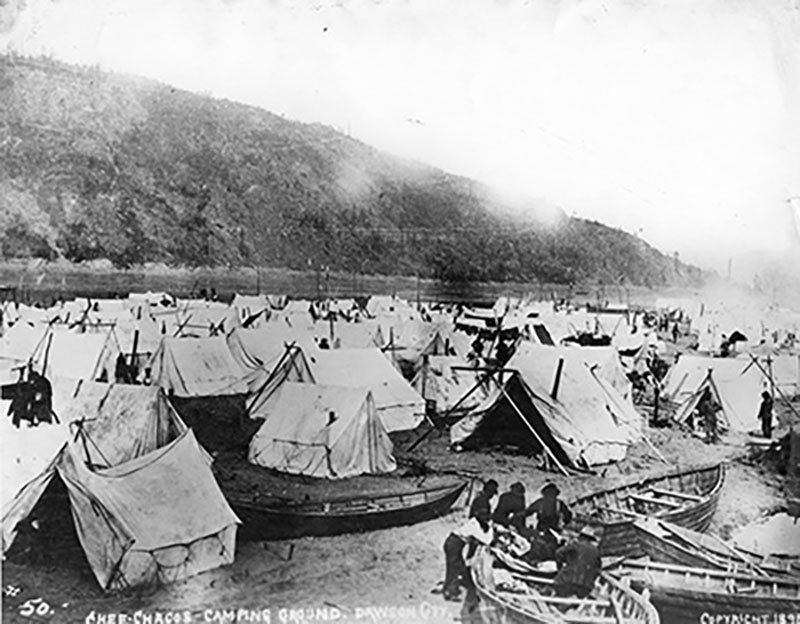

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1970.2.1.9

"The Beckoning Hand of El Dorado": Daily Life in the Gold Fields[13]

Most of the people who went north in search for gold had little intention of staying. Their purpose for the journey was to find their fortune and return home to a life of luxury. The reality was often more challenging, and only a small portion of the prospectors struck it rich. Many never made it to the gold fields, turning back due to hardship, stopping in another town along the way, or even dying from the many dangers they faced on the journey. For many travelling from California, this was their first experience of snow. Of the estimated 100,000 people who left for the Klondike, only an estimated 30,000 actually made it to Dawson City.[14]

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1962.6.4

"What’s a Fourth [of July] without fireworks? We had them too, but the beautiful colour effect was lost entirely in the daylight."[15]

The frontier society in the gold fields was a harsh and often lonely one. In Dawson City, miners who missed their own children doted upon young children and especially babies. New mothers were brought foodstuffs and even gold nuggets, and one described how even the “roughest-looking” of the miners “wanted to hold [my baby], to see his toes, [and] to feel his tiny fingers curl in their rough hands.[16]

American immigrants left their mark. Present day Moodyville, a suburb of North Vancouver, is named after Sewell Prescott Moody, a lumberman from Maine who operated a sawmill on the north shore of Burrard Inlet in 1862.[17] Further north and decades later, Canada’s second female Member of Parliament was Kansas native Martha Black, who had arrived in the Klondike in 1898. During her lifetime Black was known alternatively as the Mother of the Yukon, the First Lady of the Yukon, and Mrs. Yukon.[18] Most of the people who stayed did not have such a legacy, but for the small towns and growing cities they inhabited, their influence was extraordinary.

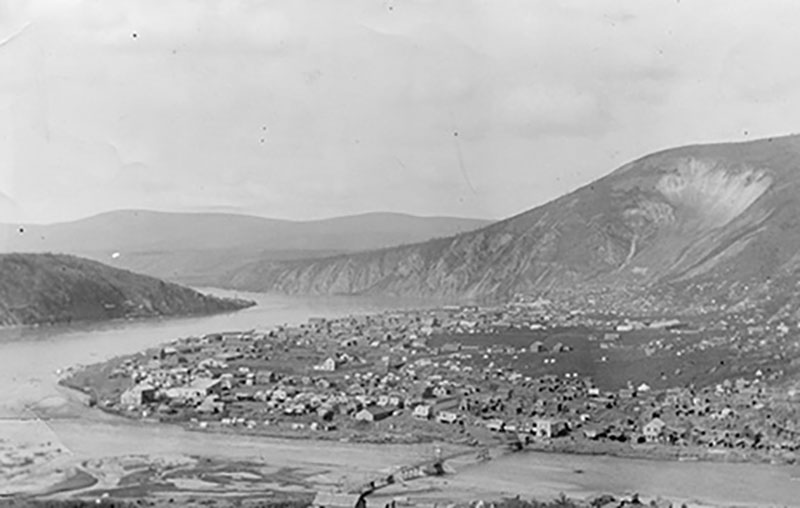

"The March of Discovery and Improvement": Development in the Gold Fields[19]

The gold rushes in British Columbia and the Klondike prompted massive changes in a very short period of time. The increase of population to the Fraser Canyon in 1858 led to the remote fur trading region becoming a formal British colony, partly to assert exclusive British control over the valuable resources. Infrastructure like roads and buildings were required in order to accommodate the growing population. Transportation corridors were completed, including a road and boat system through Harrison Lake in 1859, and a wagon road into the interior in 1864. But these projects also drove the colony into debt. An agreement with the Dominion of Canada to pay that debt helped sway British Columbia to join Confederation in 1871.[20]

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1994.15.3.54

Did You Know?

Travel on the newly constructed White Pass and Yukon Route Railway (1899) cost 25 cents per mile. It was estimated at the time to be the most expensive train travel in the world.[21]

The discovery of large deposits of gold in British Columbia encouraged prospectors to branch out through the colony, hoping for the next big strike. Searching far-flung creeks and rivers, they had variable success, and for the rest of the century boom towns sprang up around promising deposits of gold and other minerals. Most of these towns lasted only as long as the mines survived, but they prompted the development of infrastructure and the continuing colonial exploration of British Columbia.[22]

Some of these prospectors made their way into the Yukon as early as 1873. Steadily increasing numbers of American miners in the area prompted the Dominion government to establish a formal presence in the area, and a contingent of North-West Mounted Police was sent in 1895. These officers were responsible for anything from registering gold claims to mail delivery. The major gold rush in 1897 stretched their resources thin, encouraging the Dominion government to create a separate Canadian territory in 1898 with its own territorial government, and marking the entry of the Yukon Territory into Confederation.[23]

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1984.76.1.13

"The Rush of Civilization": Aboriginal Peoples and the Gold Rush[24]

The gold rush had a devastating impact on Aboriginal peoples. Traditional hunting and fishing grounds were overwhelmed by incoming miners and seized for the development of gold rush settlements. Miners also brought European diseases such as smallpox. In just one year in British Columbia, about 62 percent of the overall Aboriginal population was killed by the disease, with an even higher number on the coast (90 percent).[25] In addition to immediate population losses, diminished access to hunting grounds and the segregation of Aboriginal peoples on reserves saw Aboriginal leaders, in the years following the gold rushes, repeatedly protesting to officials that their children faced starvation.[26]

In part, the disregard of the colonists for the well-being of Aboriginal peoples was because of a prevailing idea in colonial British Columbia that Aboriginal Peoples were a “dying race” that would inevitably disappear, swept away by the might of civilization.[27] As a result, they were purposefully excluded from white society. When the Han people in the Klondike were relocated to a reserve shortly after the gold rush began, the Dominion government gave them no assistance. In fact, when the Commanding Officer for the North-West Mounted Police arrived at Dawson City, he did so with a firm directive from the Dominion government to not treat the Han "in any way which would lead them to believe that the Government would do anything for them as Indians."[28]

Power in these regions did not go uncontested. For example, the Nlha7kápmx living in the Fraser Canyon of British Columbia had to cope with the unprecedented invasion of well-armed, aggressive miners suddenly in their midst. The Nlha7kápmx were determined not to see the same fate as indigenous peoples living in California during the 1849 gold rush, where the population was systematically decimated. For many of the miners entering the Fraser River from California, good “Indians” were dead ones. The Nlha7kápmx, who considered the Fraser river and its resources theirs, initially restricted the miners from going too far upriver. The resulting confrontations led to “a great many” Aboriginal people killed, according to one miner who was there at the time. Fortunately, the impulse for eliminating the Nlha7kápmx was a minority view, with the majority favouring using the threat of force to secure peace treaties. These treaties had no official legal standing, but were made as a placeholder until land could be peacefully obtained.[29]

"There’s gold, and it’s haunting and haunting"[30]

Did You Know?

In Dawson City in 1903, pennies, nickels, and dimes were considered worthless: the smallest coin a shopkeeper would accept was a quarter.[31]

The discovery of gold in western Canada in the second half of the nineteenth century prompted a wave of immigration that transformed the region and drastically changed the lives of Aboriginal peoples. Many of these newcomers were American, and most had little intention of staying in the goldfields beyond the time it would take for them to discover their fortune. We do not know exactly how many chose to stay, but those who did found themselves adjusting to a new life that extended beyond the goldfields. They became merchants, farmers, entrepreneurs, and early inhabitants of the communities that emerged from the rush.

Credit: Dawson City Museum, 1962.7.109

In some ways the Americans who came for the gold rush entered into a land far removed from anything they had previously experienced. Not only was the journey difficult, but they found themselves in a region dominated by a British style of administration, with British customs. Though it was not all strange to the newcomers, the gold fields were remote, and making a living was a challenge. Relocating to such an isolated, inhospitable setting created formidable obstacles, but the prospect of gold and a new life gave reason to try.

Timeline:

15 June 1846 - The Oregon Treaty is signed resolving the Oregon boundary dispute. The 49th parallel is established as the boundary between American and British territory, putting the future Fraser Canyon goldfields within British possessions.

24 January 1848 - California Gold Rush begins. The discovery of gold in January 1848 led to the arrival of around 300,000 miners over the next couple of years.

1849 - The crown Colony of Vancouver Island is established with Fort Victoria at its centre. A remote outpost under the governance of the Hudson Bay Company, Fort Victoria only had about 500 white residents when the gold rush began in 1858.

April 1858 - News breaks of gold in the Fraser Valley. Fraser region experiences a massive increase in population as an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 people rush north from the western United States.

2 August 1858 - The crown colony of British Columbia is created. The mainland colony of British Columbia is established to function independently of the Hudson Bay Company, and was directly responsible to the British government.

May 1860 - The Cariboo Gold Rush begins.

12 April 1861 - The American Civil War begins.

1862-1865 - The Cariboo wagon road is constructed. The wagon road provided a relatively quick and accessible means to access the interior of British Columbia from the coast.

15 August 1866 - The colonies of Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia are amalgamated.

1 July 1867 - The Dominion of Canada is created.

15 October 1871 - British Columbia joins Confederation.

1873 - The first gold prospectors enter the Yukon. These gold prospectors were career miners, and created small settlements near the river.

1886 - The first gold stampede in the Yukon. A miner discovers a relatively large gold deposit on the Fortymile River, and establishes the town of Forty Mile.

1887 - William Ogilvie travels to the Klondike to survey the region.

1895 - The North-West Mounted Police arrive in the Yukon.

16 August 1896 - Bonanza Creek Discovery. American prospector George Carmack, his wife Kate, and her brother “Skookum Jim” discover gold on Bonanza Creek, triggering the Klondike Gold Rush.

1897 - Dawson City is formally established as news of gold breaks out.

13 June 1898 - The Yukon Territory is established and joins Confederation.

September 1898 - Gold is discovered in Nome, Alaska. Between 4,000 and 7,000 people leave Dawson City the following spring.

1899 - The Klondike Gold Rush ends. Although the initial rush was over, many families remained in the region, and people continued to immigrate.

- Full quote: "One young fellow, a boy of about twenty, tells how he came to be here. ‘I was in Seattle at the time, and I just wrote home that I was going in with all the rest of the crowd of crazy fools.’ " Tappan Adney, The Klondike Stampede (New York: Harper Brothers Publishers, 1900), 157.

- Robert Service, “The Spell of the Yukon,” Songs of a Sourdough (Toronto: William Briggs, 1907), 15.

- Julie Cruikshank, “Images of Society in Klondike Gold Rush Narratives: Skookum Jim and the Discovery of Gold,” Ethnohistory 39, 1 (Winter 1992), 25; Frances Backhouse, Children of the Klondike (Vancouver: Whitecap, 2010), 26.

- Coffee and Pies: Tappan Adney, The Klondike Stampede (New York: Harper Brothers Publishers, 1900), 346.

- Backhouse, Children of the Klondike, 30-31.

- Agnes Dean Cameron, The New North: An Account of Woman’s 1908 Journey Through Canada to the Arctic (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1986), 38.

- Martha Louise Black, My Seventy Years (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1938), 94.

- Christopher Herbert, “White Power, Yellow Gold: Colonialism and Identity in the California and British Columbia Gold Rushes, 1848-1871” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2012), 182.

- Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 69.

- Amor De Cosmos, “The Tynemouth’s Invoice of Young Ladies,” The Daily Colonist, 11 September 1862, 3.

- John Douglas Belshaw, Becoming British Columbia: A Population History (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009), 93.

- Backhouse, Children of the Klondike, 161

- Kinahan Cornwallis, The New El Dorado, or British Columbia (London: Thames Cautley Newby, 1858), 25.

- Pierre Berton, Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896-1899 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1972), 396.

- Martha Louise Black, My Seventy Years (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1938), 148.

- Martha Louise Black, My Seventy Years (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1938), 132.

- Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 87.

- Martha Louise Black, My Seventy Years (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1938), 241; Martha Louise Black, My Ninety Years (Anchorage: Alaska Northwest Publishing Company, 1976), 153.

- Cornwallis, The New El Dorado, 315.

- Jon Tattrie, “British Columbia and Confederation,” The Canadian Encyclopedia: Historica Canada, last modified 20 February 2015, accessed 22 November 2015 http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/british-columbia-and-confederation; Ficken, Unsettled Boundaries, 63, 98.

- White Pass and Yukon Route: Tappan Adney, The Klondike Stampede (New York and London: Harper Brothers Publishers, 1900), 385.

- Adele Perry, On the Edge of the Empire: Gender, Race, and the Making of British Columbia, 1849-1871 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 14.

- Michael James Brand, “Transience in Dawson City, Yukon, During the Klondike Gold Rush,” (PhD diss., Simon Fraser University, 2003), 87-8.; Jon Tattrie, “Yukon and Confederation,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, last modified 20 February 2015, accessed 22 November 2015. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/yukon-and-confederation/

- Cornwallis, The New El Dorado, 156. The impact of the gold rushes on Aboriginal peoples is essential to any narrative on the subject. For a thorough study of miner-Aboriginal violence, see Daniel P. Marshall, “American Miner-Soldiers at War with the Nlaka’pamux of the Canadian West,” in Parallel Destinies: Canadian-American Relations West of the Rockies, eds. John M. Findlay and Ken S. Coates (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 31-79).

- Perry, On the Edge of the Empire, 111.

- Cole Harris, The Reluctant Land: Society, Space, and Environment in Canada Before Confederation, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 437.

- Cornwallis, The New El Dorado, 156.

- Charlene Porsild, Gamblers and Dreamers: Women, Men and Community in the Klondike (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998), 48.

- Sources in this paragraph include: Cole Harris, "The Fraser Canyon Encountered," in The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on Colonialism and Geographical Change (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997), 110-112; Edward D. Castillo, California Indian History, Native American Heritage Commission, Retrieved November 2015. http://nahc.ca.gov/resources/california-indian-history/ Mark Forsythe and Greg Dawson, The Trail of 1858: British Columbia’s Gold Rush Past (Madeira Park B.C.: Harbour Publishing, 2007), 32, 33, 88; Cole Harris, The Reluctant Land: Society, Space, and Environment in Canada Before Confederation, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008), 432; Ficken, Unsettled Boundaries, 77, 104-105; Jean Barman, The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 162; Daniel P. Marshall, “American Miner-Soldiers at War with the Nlaka’pamux of the Canadian West,” in Parallel Destinies: Canadian-American Relations West of the Rockies, eds. John M. Findlay and Ken S. Coates (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 39.

- Robert Service, “The Spell of the Yukon,” Songs of a Sourdough (Toronto: William Briggs, 1907), 18.

- Dawson City: Reminiscences E/E/St 71, BC Archives (1908).